Reminder: We’re holding a free live Sovereign Finance discussion on Sunday 22nd June, at 7.30PM on Zoom. We’ll discuss global trends, things you might do, and answer questions from the podcast so far. Register for free here.

Rob’s comments below are in italics.

Derek’s comments below are in normal font.

I’d like to discuss how interest rates would work in a sane world, and how they have in fact been working for at least the last couple of decades. Plus, how this relates to the unfolding of geopolitical shifts that we're in the middle of.

Interest Rates…

In theory, the way it used to work, when I was working in the financial industry around 1970, prevailing interest rates were determined mainly by market perception. When I talk about interest rates, it applies to all these things: bank loans, mortgages, the rest of it.

I'm primarily discussing the bond market, particularly the government bond market. There are several elements in theory that lenders and borrowers can agree on regarding a rate of interest.

The core rate, if you like, is what the market is prepared to rent the use of money for a duration.

That obviously, like anything else in the market, is determined by supply and demand, the rate between people wanting to borrow money and people having surplus money to lend. Historically, the core rate has been approximately 2.5%. So if you had a million pounds that you'd lent out, you'd be getting £25,000 a year interest on it.

Additionally, you must consider a few other factors. One of them is the borrower's reliability. How confident the lender is that the borrower will continue to make the interest payments. Whether they're going to be in a position to repay the loan at the end of the period or over the period, depending on the way it's structured. That is, you have an insurance element.

Suppose a lender had 100 borrowers to whom they were lending money, and they expected that one in 20 of them would default. Then, they'd need to have an additional payment for the interest they were collecting. To reconcile them for the situation where one of those borrowers had defaulted. You can see that the more likely it would be to default the higher the interest rate that you'd want to allow for that.

Then, a third factor is whether the money you're going to get back will be worth as much as the money you lent out at the beginning of the period. Which of course, in times of inflation, you can guarantee that it isn't. So you'd have to take a view.

That would determine an additional premium that you'd have to allow, which obviously, if nobody knows the future, you'd have to take a view on what the likely rate of devaluation of the currency or rising prices is. Which is the way around you tend to look at it. Historically, government debt has been generally regarded as more stable and reliable for repayment and servicing than commercial debt.

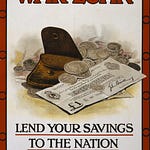

For the two or three hundred years, the British government was able to issue bonds that typically paid out around the two and a half percent basic core money rental rate. They were even able to issue bonds which had no period during which they would be guaranteed to be redeemed. There were two main classes. One was called consols, short for a consolidated loan portfolio. They had a nominal interest rate of two and a half percent. The other one was a war loan, which was issued to fund the First World War, although the actual funding was a bit of a scam as it turned out. They had a nominal interest rate of three and a half percent.

Can we just cover why that was a scam?

It was a scam because, prior to the First World War, when it was issued, it was not taken up by members of the public who wanted to take advantage of the extra 1%. There wasn't a great deal of conviction among the property-owning classes of England that they knew how well the war would turn out. Of course, it turned out disastrously for Britain, even though we supposedly won it, or our group of allies won it.

So we're told anyway…

Yeah, Britain had greatly impoverished itself. It had also lost a great deal of its manpower disproportionately amongst the bright, well-educated young men who became junior officers and bravely led their platoons into assaults on machine gun nests. Of course, the enemy soldiers took great pains to shoot the officers if they could identify them.

Anyway, although the loan wasn't taken up very widely, the Bank of England loaned three and a half million pounds, which was the amount they were trying to raise, to two of its senior employees. These employees then used the loans to purchase £3 million worth of government stocks. So, from a balance sheet perspective, the Bank of England was square. From a balance sheet point of view, their senior executives were square.

Let's assume that the bank started out with whatever capital it had. At the end of this exercise, it had assets of three million pounds, consisting of the loans that it had lent to these two individuals. The individuals lodged the bond certificates with the bank as security for the loan. The bank had an asset in the form of the loan to these purchasers and a liability in the amount of the money it had lent. They had on the face of it an asset of three million pounds worth of government bonds and a liability of a three million pound loan to the bank, which cancel each other out, leaving them with a balance of zero on that account.

However, the government then had three million pounds to spend on weapons, ammunition, uniforms, boots, and paying the soldiers, which, of course, explains why by the time the war ended, the country was in a disastrous economic position. The attempts by Winston Churchill, who was the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1920s, to put Britain back on the gold standard at the pre-war rate caused an immediate run on the pound which led to the general strike. Anyway, so getting back...

These government bonds that were yielding two and a half or three and a half percent by 1970, we'd got something like inflation running at 10% or so. Of course, it went on and up from there. Consequently, nobody was going to pay a hundred pounds for a hundred pounds nominal version of British bonds that were only paying two and a half percent interest.

As a result, the interest rates prevailing on government bonds increased to around 16%, which meant that people's bank loans, consumer credit, and mortgages rose to even higher levels than that.

Consequently, if you've got a bond that pays a nominal 3.5%, and the prevailing rate of interest you're looking for is about 16%, you'd have to buy or sell that £100 nominal bond for about £16. That would yield approximately 16% on your investment.

Now, of course, people who bought bonds at that price in 1970 and hung onto them would have been able to see their price go up to over the £100 nominal in the early 2000s.

The British government thought it would be a smart move at this time of very low interest rates to redeem those bonds, as new government debt was being issued at around 2% in 2009 and 2010. So, bonds in the market that had a nominal interest rate of 4% were selling for £50 on the nominal £100 bond. Is that clear? How does that mechanism work? If the prevailing interest rate increases, the bond price decreases. If the prevailing interest rate decreases, the bond price increases.

Yeah, because the nominal bond price was fixed in the past.

Which will be the price when it's redeemed. Until very recently, that has been sustained. Of course, the way it's been sustained is by the Federal Reserve effectively printing more and more money and the other central banks doing likewise.

Yes, the “Magic Money Tree”...

Yeah. Of course, all good things must come to an end. Just recently, United States bonds have been downgraded from their AAA rating. The US Treasury is finding it increasingly difficult to attract buyers for new issues of bonds. At the same time, foreign US bondholders have been trying to strike a balance.

Probably looking at Russian bonds instead!

Well exactly. The holders, probably the biggest foreign holders of US bonds, are the Chinese. I don't know how they compare with the Saudis, but the Saudis have huge holdings, as do the other oil-exporting states, due to the arrangement that Kissinger made with them in the 1970s. They agreed to sell their oil for dollars and then use those dollars to buy various assets, primarily US treasury securities, because gold would not yield them any interest, and they would get interest payments on the government bonds.

Of course, this assumes that the purchasing power of the dollar at the end of the loan period will hold up and that the assets are sound. When the United States immediately confiscated Russian assets on the invasion of Ukraine, it must have given other US bondholders cause for thought. Well, maybe that could happen to me, too, which makes it a bit less attractive to hold them.

Meanwhile, to stimulate the economy, as they say, the Federal Reserve is attempting to keep interest rates low. Obviously, when interest rates go up, people have more outgoings, particularly if they're highly leveraged with a lot of borrowing. They don't have so much money to spend on goods and services.

To help keep the economy moving, the Federal Reserve has been attempting to keep interest rates low. It can only do this by flooding the market with more and more dollars. Of course, as it floods the market with more and more dollars, more and more people will be concerned about inflation.

So it could be that the confidence trick, really the only way I can describe it, whereby America has been buying goods from the rest of the world and paying them in this newly printed funny money without having to redress the balance, maybe coming to an end. Against this background, we've got 36 trillion of American government debt. If prevailing interest rates rise, the amount the American government will have to pay in interest will increase accordingly.

There are only two sources of government spending. It can either come from selling more government bonds or from taxation. The American population is probably not in a position to be paying more taxes, especially if they're subjected to rising prices in every direction.

The ability to refinance loans as they mature by issuing new bonds may simply not be available. Foreign holders of US bonds are in a difficult position. If they rush to sell their existing holdings, it will crash the price and reduce the return they can get from liquidating those bonds. However, if they don't, they may end up being saddled with them anyway, as the price plummets.

The real significance of this is that, because America has spent the last 20 years hollowing out its industrial base and manufacturing capabilities, it has been cheaper to do so in China...

Or wherever, yeah.

Or Mexico or Vietnam or wherever. America has very little to export apart from, well, I don't think it has a great agricultural produce surplus over what it needs to feed its population these days. The only other thing it has to export is arms.

Ironically, of course, it's not even getting cash for a lot of the arms that it's exporting because these are being subsidised by American taxpayers for ostensibly geopolitical reasons. Essentially, this is a transfer of wealth from the general population into the pockets of arms manufacturers. So we could well find that America simply no longer has the wherewithal to pay its government employees, to maintain its infrastructure, in particular to pay its military personnel, maintain all its overseas bases and continue to run that protection racket, to put it bluntly, which has been operating since the Second World War.

It's a globe-spanning setup as well, isn't it? If you think about all of the military bases across the world.

Yes, there are about 800 of them altogether. So, meanwhile, we've got Starmer and Macron and Scholz and Merz all suggesting that we should be ramping up our investment in our armaments, which, as we pointed out before, is not creating any wealth.

It is putting money in the pockets of the people who happen to be employees or contractors of the arms manufacturers, so that they can go out and spend. Unless we're actually producing the goods that they're going to buy, they'll be spending that abroad. That will be an additional drain on the economy. So my point is that these things could reinforce one another. It could unravel very much more rapidly than anybody seems to imagine.

Sounds like a perfect storm, doesn't it? The end of the road appears to be a lot closer than it seems.

I would say so. We'll watch this space.

Share this post