Rob’s comments are in italics.

Derek’s comments are in normal font.

We're going to reminisce about your past today and explore some of the lessons from working in finance. So what happened and where do we need to start?

When I came down from university, I got a job in a firm of stockbrokers. It was one of the large firms, had about 40 partners and 400 staff. Its primary business was for institutions, for pensioners funds, unit trusts, fund managers of all sorts.

One way or another, I concluded after about 18 months that this wasn't a life I wanted to pursue for various reasons. However, in the course of that, I did actually get quite a lot of insight into that entire world. I have also kept an eye on the way that it's developed over the years.

This was 1969, 1970. It was a very different world then. It was much more leisurely. The office hours were 9.30AM to 5.30PM with a healthy one hour lunch break. Really keen, ambitious people came in at nine o'clock instead of 9.30 to catch up on current financial events, but not anything like the tempo that exists in that world these days. Also, I think to a large degree, it was essentially an ethical environment. I mean, there were a few wide boys, but the majority of people working in stock broking and in merchant banking and in fund management were genuinely trying to do a good job. They were genuinely providing a useful service.

For instance, the whole thrust of this was to provide people who wanted to have effective savings and investment plans over the course of their lifetime for those to perform well. In particular of course for people who wanted to contribute either themselves or from their employers into a fund which would provide them with an income in retirement. They managed to do that in an effective way.

Certainly with all the employers schemes, they were defined, they were what were called defined benefit schemes. They provided for two thirds of, typically two thirds of your final salary, assuming you'd spent a full time, working lifetime in that scheme for the rest of your life.

The mechanics of this is pretty simple. There was an accumulation phase and a drawdown phase. The accumulation phase was obviously over the course of the years that you're working. You paid a proportion, maybe typically 10% of your gross earnings into the fund. The fund was invested to grow according to the laws of compound interest over the course of the lifetime. Then when you retired, it was put into an annuity, which is essentially like a life insurance policy in reverse, whereby the value of the fund was put into that annuity. That provided a certain percentage of the fund every year for as long as you lived. Of course some people lived for quite a long time, other people didn't survive very long after retiring. But it averaged out so that worked out. There was no asset at the end of that.

There was a big shift where instead of being the so-called defined benefits scheme, such as that, people were persuaded to pay into defined contribution, which obviously is exactly what it says. You define how much you're paying into it, but you were left at the whims of the performance of the financial markets as to what you actually got in the end.

A great many of us have found that we didn't get nearly as much as we were expecting. There are various reasons. One is the changes in the taxation treatment of pension schemes that was slipped in by Gordon Brown when he first became Chancellor of the Exchequer. In order to balance his budget, he needed to raise more taxation. The Labour Party promised not to raise taxation. So rather than doing it in an honest way, he raised the taxation by cancelling the benefits of pension schemes banking on the fact that people would not notice this because it didn't affect their immediate financial situation on a current basis.

However, if you're taxing the income which is being accumulated in the fund over the years, that makes a significant difference. Because it's relying on compound interest, it means that there's going to be a lot less in the fund. The other thing is that the large corporations which comprise the majority of the shareholdings that in the funds are invested in are not nearly as generous with dividends as they had been historically. More of the profits from the corporation are being transferred to executives and directors of the companies. More of it is going into the so-called financial industry that's managing these things. So it's a lot less beneficial for the typical normal person who's looking forward to a retirement income.

I used to have a client who was an independent financial advisor. He described it as being like the ‘goo’, the financial industry that sucks everything up if you just leave it.

Partners of a successful stock-broking firm or merchant bank had pretty substantial incomes. They might have been earning five or 10 times the earnings of a doctor, for example. But they weren't earning 100 or 1,000 times the income of a doctor, which top financiers are doing these days.

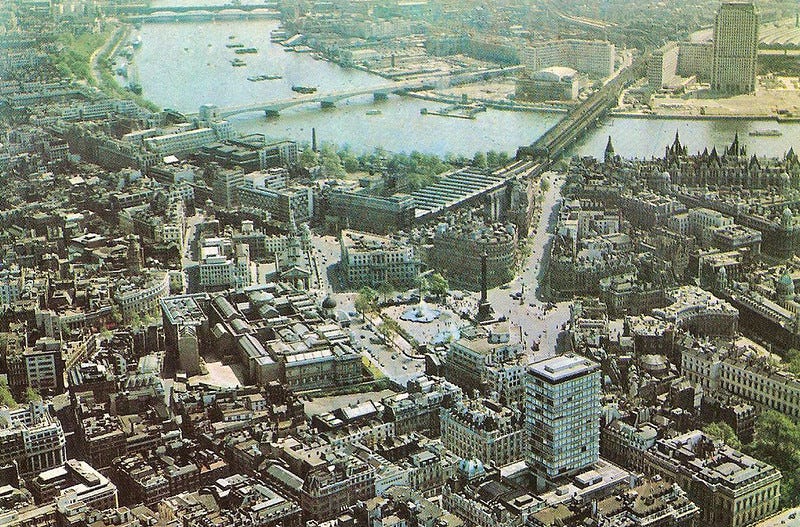

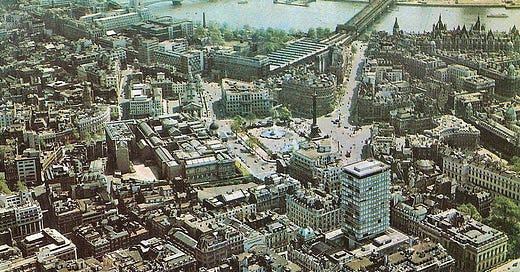

The number of people in that segment of the economy has ballooned out of all proportion. I think there were 2000 members of the stock exchange in those days. They probably have a staff of about 10 times the number of principals. For instance, my firm, as I said, it had 40 partners and it had a staff of about 400. If you were small stockbroking with two or three partners, you'd probably have 20 or 30 staff. So that would have meant that there were a total of 20,000 or so people working in stockbroking, probably a similar number in merchant banking. A similar number in life insurance and various other kinds of fund management. So perhaps 60,000 people working in the financial district. Whereas now if you look not only have you got the city which is full of skyscrapers instead of the four or five story buildings that were there back in the day. You've also got the enormous financial district over in Canary Wharf in Docklands. I don't know how many hundreds and hundreds of thousands of people are altogether involved in this industry. They're all earning far larger than average wages in other segments of the economy.

You have to ask yourself what they're actually contributing to. It's worth mentioning also that banking and stockbroking were arguably performing a useful service at that time. Okay, they were taking a small cut, but they were connecting people who had capital with enterprises which needed the capital to invest in their factories and their motor fleets and their machine tools and whatever it was they needed to run the business.

There was a beneficial effect all the way around. Whereas we've seen over the subsequent decades, more and more of it is just some form of essentially gambling, computer, essentially a gigantic casino where one person's gain is another person's loss. So that's been my perspective over the years from seeing Inside the Beast.

And that's now our biggest export.

I was thinking as you were talking about the doge happenings in the US, the Department of Government's efficiency and looking into these things and realizing that it's not very efficient and why do we have all these people. It sounds like at some point the system's going to break and a similar thing maybe has to happen.

Well, it certainly seems to be. I mean, there's no doubt that in government, especially national government, there's enormous wastage of another sort. Nevertheless, the bull in China shop approach to trying to get to grips with that which Elon Musk and Donald Trump have been applying is probably not going to get a happy outcome.

What else can people do? Is it a case of looking after your own finances where possible and taking responsibility for things more?

Once you grasp the essential principles, you need to see what is possible. This is getting into the realm of finance, but the only thing I can suggest is that you actually find a financial advisor who thinks outside the box.

A lot of so-called financial observers advise, they're glorified salesmen.

Most just sell products. They don't charge fees, they get paid to sell products. They set their fee out at the commission that they're incentivised to sell certain products. So it's not independent.

It's essential to get some orientation as to what are the possibilities as far as the taxation arrangements. These of course vary from country to country and from time to time. See what schemes there are which enable you to retain some control over it. Then learn enough about these things to be able to make an intelligent decision. See what the underlying assumptions are of the way that the fund needs to grow to meet your objectives. Be monitoring it all the time to measure up whether or not it's doing that.

Yeah, and I think a good financial advisor should help you figure out how much you actually need to do the things that you want to do as well, because you can't take it with you at the end.

Yeah, exactly so. Okay

Just on that, had a client, I think it's worth finding someone local as well, or who really understands the local environments. I had a client a few months ago who is a financial advisory in Dublin. So they specifically serve the Republic of Ireland. They say that Ireland apparently has like the most complex legal environment that you can ever imagine. So it's like they specialise in that. So find the right person, I guess.

Yeah, that makes sense.

Share this post